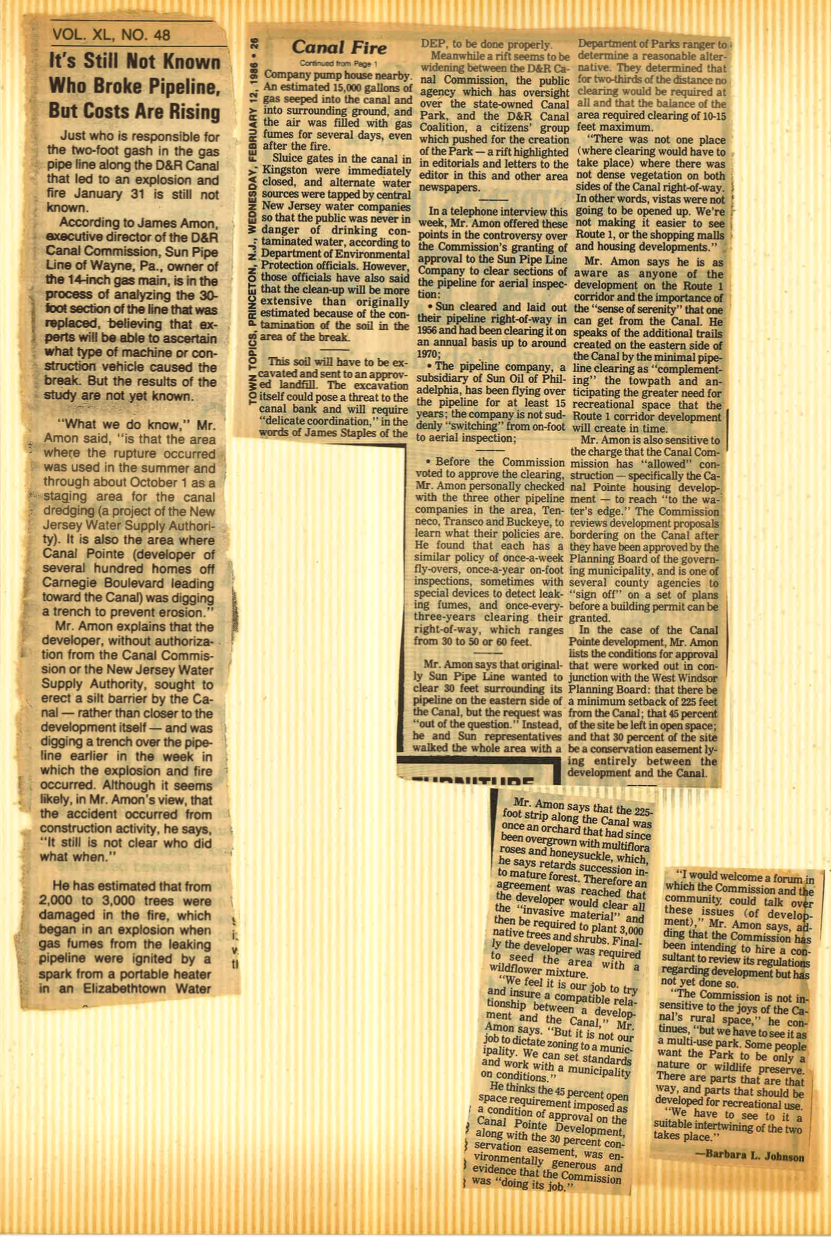

Town Topics

12 February, 1986

It’s Still Not Known Who Broke Pipeline But Costs Are Rising

Barbara L. Johnson

Just who is responsible for the two-foot gash in the gas pipe line along the D&R Canal that led to an explosion and fire January 31 is still not known.

According to James Amon, executive director of the D&R Canal Commission, Sun Pipe Line of Wayne, Pa., owner of the 14-inch gas main, is in the process of analyzing the 30-foot section of the line that was replaced, believing that experts will be able to ascertain what type of machine or construction vehicle caused the break. But the results of the study are not yet known.

“What we do know,” Mr. Amon said, “is that the area where the rupture occurred was used in the summer and through about October 1 as a staging area for the canal dredging (a project of the New Jersey Water Supply Authority). It is also the area where Canal Pointe (developer of several hundred homes off Carnegie Boulevard leading toward the Canal) was digging a trench to prevent erosion.”

Mr. Amon explains that the developer, without authorization from the Canal Commission or the New Jersey Water Supply Authority, sought to erect a silt barrier by the Canal — rather than closer to the development itself — and was digging a trench over the pipe-line earlier in the week in which the explosion and fire,, occurred. Although it seems likely, in Mr. Amon’s view, that the accident occurred from construction activity, he says, “It still is not clear who did what when.”

He has estimated that from 2,000 to 3,000 trees were damaged in the fire, which began in an explosion when gas fumes from the leaking pipeline were ignited by a spark from a portable heater in an Elizabethtown Water Company pump house nearby. An estimated 15,000 gallons of gas seeped into the canal and into surrounding ground. and the air was filled with gas fumes for several days. even after the fire.

Sluice gates in the canal in Kingston were immediately closed, and alternate water sources were tapped by central New Jersey water companies so that the public was never in danger of drinking contaminated water, according to Department of Environmental Protection officials. However, those officials have also said that the clean-up will be more extensive than originally estimated because of the contamination of the soil in the area of the break.

This soil will have to be excavated and sent to an approved landfill. The excavation itself could pose a threat to the canal bank and will require “delicate coordination.” in the words of James Staples of the DEP, to be done properly.

Meanwhile a rift seems to be widening between the D&R Canal Commission, the public agency which has oversight over the state-owned Canal Park, and the D&R Canal Coalition, a citizens’ group which pushed for the creation of the Park — a rift highlighted in editorials and letters to the editor in this and other area newspapers.

In a telephone interview this week, Mr. Amon offered these points in the controversy over the Commission’s granting of approval to the Sun Pipe Line Company to clear sections of the pipeline for aerial inspection:

- Sun cleared and laid out their pipeline right-of-way in 1956 and had been clearing it on an annual basis up to around 1970;

- The pipeline company, a subsidiary of Sun Oil of Philadelphia. has been flying over the pipeline for at least 15 years: the company is not suddenly “switching” from on-foot to aerial inspection;

- Before the Commission voted to approve the clearing, Mr. Amon personally checked with the three other pipeline companies in the area, Tenneco, Transco and Buckeye, to learn what their policies are. He found that each has a similar policy of once-a-week fly-overs, once-a-year on-foot inspections, sometimes with special devices to detect leaking fumes, and once-every-three-years clearing their right-of-way, which ranges from 30 to 50 or 60 feet.

Mr. Amon says that originally Sun Pipe Line wanted to clear 30 feet surrounding its pipeline on the eastern side of the Canal, but the request was “out of the question.” Instead, he and Sun representatives walked the whole area with a Department of Parks ranger to determine a reasonable alternative. They determined that for two-thirds of the distance no clearing would be required at all and that the balance of the area required clearing of 10-15 feet maximum.

“There was not one place (where clearing would have to take place) where there was not dense vegetation on both sides of the Canal right-of-way. In other words, vistas were not going to be opened up. We’re not making it easier to see Route 1 or the shopping malls and housing developments.”

Mr. Amon says he is as aware as anyone of the development on the Route 1 corridor and the importance of the “sense of serenity” that one can get from the Canal. He speaks of the additional trails created on the eastern side of the Canal by the minimal pipeline clearing as “complementing” the towpath and anticipating the greater need for recreational space that the Route 1 corridor development will create in time.

Mr. Amon is also sensitive to the charge that the Canal Commission has “allowed” construction — specifically the Canal Pointe housing development — to reach “to the water’s edge.” The Commission reviews development proposals bordering on the Canal after they have been approved by the Planning Board of the governing municipality and is one of several county agencies to “sign off” on a set of plans before a building permit can be granted.

In the case of the Canal Pointe development, Mr. Amon lists the conditions for approval that were worked out in conjunction with the West Windsor Planning Board: that there be a minimum setback of 225 feet from the Canal; that 45 percent of the site be left in open space; and that 30 percent of the site be a conservation easement lying entirely between the development and the Canal.

Mr. Amon says that the 225-foot strip along the Canal was once an orchard that had since been overgrown with multiflora roses and honeysuckle, which he says retards succession into mature forest. Therefore, an agreement was reached that the developer would clear all the invasive material” and then be required to plant 3,000 native trees and shrubs. Finally, the developer was required to seed the area with a wildflower mixture.

“We feel it is our job to try and ensure a compatible relationship between a development and the Canal,” Mr. Amon says. “But it is not our job to dictate zoning to a municipality. We can set standards and work with a municipality on conditions.”

He thinks the 45 percent open space requirement imposed as a condition of approval on the Canal Pointe Development, along with the 30 percent conservation easement, was environmentally generous and evidence that the Commission was “doing its job.”

“I would welcome a forum in which the Commission and the community, could talk over these issues (of development),” Mr. Amon says, adding that the Commission has been intending to hire a consultant to review its regulations regarding development but has not yet done so.

“The Commission is not in-sensitive to the joys of the Canal’s rural space,” he continues, “but we have to see it as a multi-use park. Some people want the Park to be only a nature or wildlife preserve. There are parts that are that way and parts that should be developed for recreational use.

“We have to see to it a suitable intertwining of the two takes place.”