Princeton Packet

10 May, 1988

Nassau Hall fires in 1800s test firefighters

By 1800 the fire department had in addition to the engine, three axes and 35 leather buckets on poles, all of which were kept in the engine house. Two ladders, one of them 32 feet long and one of them 21 feet long were kept at the foot of College Lane (now Prospect.) The company was also responsible for constructing and maintaining a number of public pumps and wells throughout the town.

None of this, however, proved enough when the company faced its first major test in March of 1802.

It was 1 p.m., March 6. The bell was ringing for dinner, (then served mid-day) the servant had just opened the door of the dining room and a few students had entered and were standing at their places, when the cry of fire resounded through the room. One of the students, George Strawbridge, a senior, left us a complete report of the event in his memoirs which have been saved at the Princeton Library.

Strawbridge rushed out on the campus and saw a crowd assembled there looking up at a blaze in the belfry. He says it was a matter of but a minute for him to mount the stairs to his room which was on the top floor, seize his water pitcher and empty it on the flames in the room under the cupola above his head, beside the trap door leading to the belfry.

Apparently this proved utterly futile, and at that precise moment College President Smith appeared beside him and raising his hands, exclaimed: “This is the progress of vice and irreligion.”

Strawbridge claimed the president then turned and left the room.

All attempts to extinguish the flames were useless. Once they had broken through the wooden ceiling into the belfry, the flames leaped instantly up to the bell-shaped cap and converted the whole cupola into a giant torch. It is an established fact that in this era most of the fires took place in the first three months of the year. This was the time of high winds from the west or northwest and it was during the early months of the year that roof shingles were at their driest. This particular day the wind was blowing from the southwest, but the seasoned timbers of floors and window frames and doors were highly combustible.

Strawbridge reported that the firemen were not present or at least late in arriving and that the fire engine was not adequate. There was no refutation of this report, but it was obvious from the reports that in an extremely short time the building was beyond saving. Students busied themselves with rescuing the precious scientific apparatus and what books, furniture and clothing could be brought down the crowded stairs.

Out on the campus, as the fire roared overhead, the cupola toppled and the roof crashed in. All except 100 of the 3,000 volumes in the college library, the entire libraries of two literary societies and most of the furniture and personal belongings of the students were consumed.

As evening came on, the president gazed in despair at the blackened walls and empty window spaces of the noble building in which for half a century the life of the college had centered.

It is difficult to evaluate the work of the fire company during the fire. Strawbridge clearly did not give the impression that the firefighters were of much help, but that can be no more than student/town rivalry which was keen at this time.

It should be remembered that the fire equipment was stored at some distance from Nassau Hall and at 1 pm. the various members of the company might well be expected to be at their lunches, thus adding to the time needed before they could assemble in proper order. Contemporary sketches of the event showed both firemen and the engine in place in front of the building.

What is known is that President Smith firmly believed that the fire had been the work of a small group of students who had been infected with those Jacobean principles which were tearing the bonds of society asunder and threatening to overturn the country.

He had been told that hostility to religion and moral order was one of their chief characteristics.

It is also apparent that neither the president nor the trustees behaved with much deliberation or even with logic. Strawbridge told us that “an excited com-mittee of the trustees” reported after an investigation that the “conflagration could not have been accidental.” Their proof was that the flames first appeared under the cupola, some distance from any of the chimneys; that they spread with great rapidity; that many persons detected a strong smell of turpentine; that the smoke was “dark and heavy;” that “the fire was accompanied with an unusual crackling, ” that a second flame burst from the west end of the roof at some distance from the cupola. All of this they felt pointed to the work of an incendiary.

Strawbridge undertook to make an investigation of his own and then declared that there was no reason to suspect the students “as a body or individually.”

His reasoning went as follows: The fire occurred in broad daylight; the room under the cupola was kept locked; the hallway upon which it opened was “as public as a street;” there were at that time no “Locc[…] foco” matches and no one would have dared bring fire in a shovel.

In short there was absolutely no motive for such a dastardly deed. “I really regard it as the weakest charge of incendiarism I have ever heard,” he concluded.

Strawbridge’s solution: The forger suspicion should have pointed not at the students, but at that humble individual the chimney sweep — for neglecting h duty.

Rumor had it that one of the chimney had been on fire that morning and the flames might easily have worked through an opening in the old brick work to a raft[…] or girder.

It is probable that the fire had been spreading in the attic for an hour possibly longer before it found an outlet the cupola and a few minutes later at the west eaves of the building.

Nevertheless, when a trustees-appointed committee consisting of General Beatt and Richard Stockton reported that in their opinion “the building was intentionally s on fire,” the college lost no time i suspending five or six young men. The were never charged; there was no proof given.

Fifty-three years later on the stormy night of March 10, 1855, fire again destroyed all that was combustible of Nassau Hall.

It was at 8:30 p.m. that evening where most of the students were hard at work in their rooms that the silence was broken by the cry of “Fire! Fire!” Apparently an ember had fallen from the grate in room 33-A on the second floor near the northeast corner, and in the absence of the occupant, Samuel W. Oliver of Mobile, Alabama, the flames had gained consider-able headway before the warning signal was sounded.

A high wind was blowing from the northwest and in a moment all was con-fusion — students making desperate efforts to save their belongings, firemen shouting, professors giving directions, hundreds of villagers looking up from the campus in awed silence.

Students and firemen according to one report “worked manfully side by side and when they stretched the hose to the second story and began to pour a stream upon the fire they had hope of success.” But, as another report points out, “this was long before Princeton had motor engines and a water system, and the college pumps were altogether inadequate.”

In any event the supply of water failed and a few minutes later the old building was a roaring furnace. Attracted by the glare which was visible for many miles, crowds flocked in from the countryside to see the spectacle. The high winds carried the flames to East College and Whig Hall, but quick work by students and firemen saved those buildings.

By midnight nothing was left of Nassau Hall save the massive stone walls which were according to one observer “thrown into strong relief by the glowing embers within.”

In the general confusion it was impossible to bring furniture or clothing from the upper stories, so that many of the students suffered heavy losses.

Some of the most valuable contents of the building were saved including the portraits hanging in the old chapel.

The head of Homer which is said to have been brought from England “to adorn the flat arch of the main door when the building was erected, and which had long been an object of veneration to the stu-dents” was chiseled out of its position amid the cheers of the crowd.

But the giant bell which had been recast after the fire of 1802 and which for the intervening years had summoned students to meals, classes and prayers was melted beyond repair.

The Philadelphia Society’s Library, among the finest in the nation, was burned as well.

There was no hint of incendiarism as there had been in 1802 and some of the dispossessed students consoled themselves in “riotous living” at Joline’s (a local pub). The fire did not cause the suspension of classes. Many of the students found rooms in the village; a few moved in with friends in East and West College.

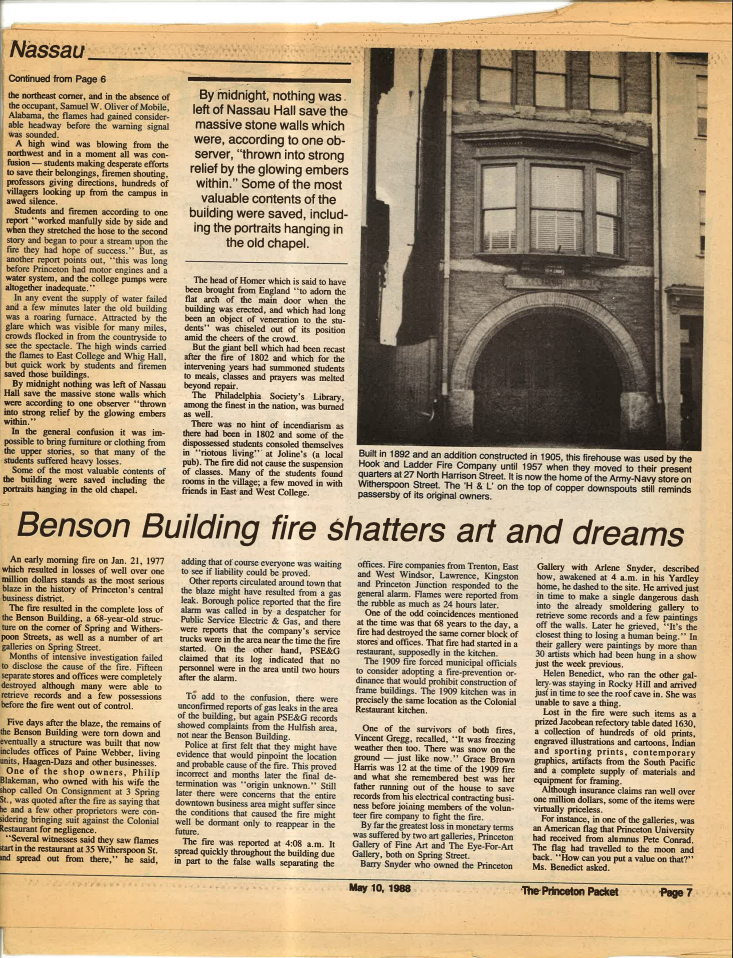

Built in 1892 and an addition constructed in 1905, this firehouse was used by the Hook and Ladder Fire Company until 1957 when they moved to their present quarters at 27 North Harrison Street. It is now the home of the Army-Navy store on Witherspoon Street. The ‘H & L’ on the top of copper downspouts still reminds passersby of its original owners.

Benson Building fire shatters art and dreams

An early morning fire on Jan. 21, 1977 which resulted in losses of well over one million dollars stands as the most serious blaze in the history of Princeton’s central business district.

The fire resulted in the complete loss of the Benson Building, a 68-year-old structure on the corner of Spring and Witherspoon Streets, as well as a number of art galleries on Spring Street.

Months of intensive investigation failed to disclose the cause of the fire. Fifteen separate stores and offices were completely destroyed although many were able to retrieve records and a few possessions before the fire went out of control.

Five days after the blaze, the remains of the Benson Building were torn down and eventually a structure was built that now includes offices of Paine Webber, living nits, Haagen-Dazs and other businesses.

One of the shop owners, Philip lakeman, who owned with his wife the hop called On Consignment at 3 Spring t., was quoted after the fire as saying that and a few other proprietors were con-idering bringing suit against the Colonial taurant for negligence.

“Several witnesses said they saw flames start in the restaurant at 35 Witherspoon St. and spread out from there,” he said, adding that of course everyone was waiting to see if liability could be proved.

Other reports circulated around town that the blaze might have resulted from a gas leak. Borough police reported that the fire alarm was called in by a dispatcher for Public Service Electric & Gas, and there were reports that the company’s service trucks were in the area near the time the fire started. On the other hand, PSE&G claimed that its log indicated that no personnel were in the area until two hours after the alarm.

To add to the confusion, there were unconfirmed reports of gas leaks in the area of the building, but again PSE&G records showed complaints from the Hulfish area, not near the Benson Building.

Police at first felt that they might have evidence that would pinpoint the location and probable cause of the fire. This proved incorrect and months later the final determination was “origin unknown.” Still later there were concerns that the entire downtown business area might suffer since the conditions that caused the fire might well be dormant only to reappear in the future.

The fire was reported at 4:08 a.m. It spread quickly throughout the building due in part to the false walls separating the offices. Fire companies from Trenton, East and West Windsor, Lawrence, Kingston and Princeton Junction responded to the general alarm. Flames were reported from the rubble as much as 24 hours later.

One of the odd coincidences mentioned at the time was that 68 years to the day, a fire had destroyed the same corner block of stores and offices. That fire had started in a restaurant, supposedly in the kitchen.

The 1909 fire forced municipal officials to consider adopting a fire-prevention or-dinance that would prohibit construction of frame buildings. The 1909 kitchen was in precisely the same location as the Colonial Restaurant kitchen.

One of the survivors of both fires, Vincent Gregg, recalled, “It was freezing weather then too. There was snow on the ground — just like now.” Grace Brown Harris was 12 at the time of the 1909 fire and what she remembered best was her father running out of the house to save records from his electrical contracting business before joining members of the volunteer fire company to fight the fire.

By far the greatest loss in monetary terms was suffered by two art galleries, Princeton Gallery of Fine Art and The Eye-For-Art Gallery, both on Spring Street. Barry Snyder who owned the Princeton Gallery with Arlene Snyder, described how, awakened at 4 a.m. in his Yardley home, he dashed to the site. He arrived just in time to make a single dangerous dash into the already smoldering gallery retrieve some records and a few painting off the walls. Later he grieved, “It’s the closest thing to losing a human being.” It their gallery were paintings by more that 30 artists which had been hung in a shots just the week previous.

Helen Benedict, who ran the other gallery. was staying in Rocky Hill and arrived just in time to see the roof cave in. She was unable to save a thing.

Lost in the fire were such items as a prized Jacobean refectory table dated 1630, a collection of hundreds of old prints, engraved illustrations and cartoons, Indian and sporting prints, contemporary graphics, artifacts from the South Pacific and a complete supply of materials and equipment for framing.

Although insurance claims ran well over one million dollars, some of the items were virtually priceless.

For instance, in one of the galleries, was an American flag that Princeton University had recieved from alumnus Pete Conrad. The flag had travelled to the moon and back. “How can you put a value on the that?” Ms. Benedict asked.