Princeton Packet

17 July, 1984

Squad work keeps university students in touch with life

by Charles Stile

Staff Writer

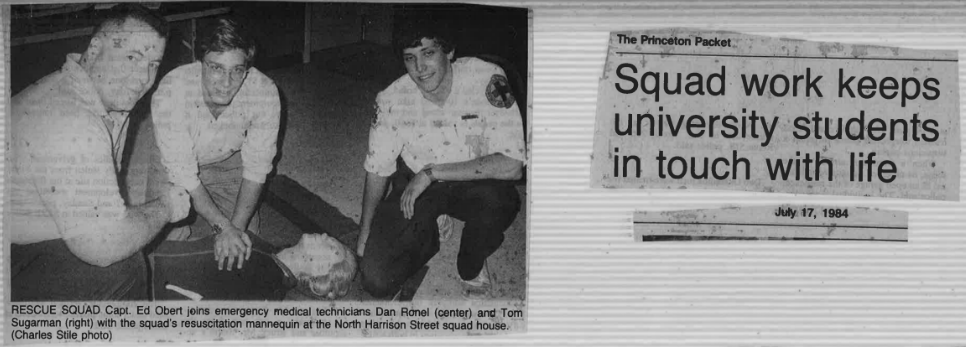

When most Princeton University students cross Nassau Street, it’s usually to go to the movies, go shopping, or to get something to eat. But for junior Dan Ronel and senior Tom Sugarman, it could mean the difference between life and death for someone in the area.

The two are emergency medical technicians and quite often their destination is the Princeton First Aid and Rescue Squad building on Harrison Street.

They are two of many university students during the past 14 years who have taken the liberty of adding the rewarding, but sometimes perilous, rescue squad experience into their educational regimens and into their personal character.

“I joined on impulse,” said Mr. Rood, a biology major. “And I became addicted after my first call.” He had to assist with a cardiac arrest victim.

“There was so much going on around me that it took me almost a week to absorb everything,” he said. “I realized that this was something that I could do with my hands and that I could do physically and directly to help somebody instead of raking leaves.”

Although the campus is a mile away, the type of training that the university and the squad provides are almost worlds apart, according to the two students.

“It (squad experience) teaches you, in a way, helplessness,” Mr. Rohel said. “At the university you are taught no matter if you work really hard, you’ll get good results. And here you work, as hard as you want to make someone feel better or even save a life and you can just watch them die.”

Ed Obert, the squad captain said. “I have seen some character developments, things that are going to be an asset later on, and things they learned here that they are not going to get on campus.”

Working with others, under stressful conditions, “learning how to take the heat— and knowing when to give it sometimes,” and having a sense of diplomacy during tense times are some of the the character building lessons the Students learn at an accident site or on the back of a squad vehicle.

MR. OBERT believes that the university life prevents the students from learning these qualities.

“I would go as far as to say that they, (the university) hinder it.” he said. “Because at a time when people their age are out dealing with the public, they are not. They are sheltered and that is a handicap.”

“Unless you get involved in a university sponsored volunteer service, that’s correct.” agreed Mr. Ronel. Students can face the outside world as tutors or temporary teachers while attending school. But “nothing gets as involved as this, or takes this much out of you as this.” he said.

Administering care to a victim is not the only time-consuming rescue squad requirement, according to Mr. Obert. Before anyone joins the squad, they must become emergency medical technicians by putting in 100 hours of training in a state Department of Transportation course.

For Mr. Sugarman, a senior who began riding with the squad at the end of his sophomore year, the differences between the experience taught by the course and what actually happens in real life is similar to what Mr. Ronel and Mr. Obert see as the differences between thc real world and the university.

It’s easy to read a book, it’s easy to play with manikins,” he said. “It’s easy to check a manikin’s pulse because it’s not there and it’s never going to be there and it’s never going to have one. But you wonder what it is like to check your first person’s pulse and not have a pulse. If you don’t feel it, you question yourself whether your hand is in the right place. When I went through the course, I looked forward to joining the squad to learn the practical aspects of it.”

“There is nothing hard about it,” Mr. Obert said of the course. “It’s time consuming. But once they get through with it, they are prepared. It takes the novice and makes him into a technician.”

Time is a valuable commodity, especially on the competitive Princeton University campus. But both Mr. Ronel and Mr. Sugarman have no problcm arranging their schedules to meet their rescue squad duties.

“I think I missed one class the entire year to go on a call,” said Mr. Sugarman, who has had to cut down most of his Thursday night social activity because of his squad involvement. “I suppose I could blame the squad for not getting my homework done, but that is not really fair.”

Mr. Ronel, who has time available to participate in the squad due to an athletic injury, thinks that the work on the squad is an escape.

“It’s a very necessary release, because if you don’t get out from living at the university 24 hours a day, you can get stifled.” he said. “When you are on a call, you can’t think of anything else. You leave your books behind you.”

Life on the squad is also filled with unpredictable challenges, and Mr. Ronel said it is that quality that keeps him coming back.

“Every day there is another challenge,” he said. “‘You become better and deal with the situation better. That’s the factor of addiction. There is always a challenge.”

And of course, both Mr. Ronel and Mr. Sugarman have been bitten by what Mr. Obert calls the “bug of helping others,” another requirement for a successful rescue squad tenure.

“When I first started on the squad, I used to call it a sacrifice,” Mr. Ronel said. “But I get so much pleasure out of this than doing any other extracurricular activity I do at school, that it has not become a sacrifice anymore. There is no greater feeling than helping someone.”

Photo captions: Rescue Squad Capt. Ed Obert joins emergency medical technicians Dan Ronel (center) and Tom Sugarman (right) with the squad’s resuscitation mannequin at the North Harrison Street squad house.

Photo credit: Charles Stile