Town Topics

30 June 1982

Volunteer Fire Companies Find It a Hard Day’s Work Fighting Serious Fires in Training Exercises in Burlington

The smoke is thick. In a sudden attack, it sends a hundred sharp needles into your eyes. You’re as close to the dark floor as you can get, surrounded by a black smothering blanket. You hear the whoosh as water surges from the hose. Your helmet and coat keep you dry.

“If you think you’re going to be sick, get out.” The flat voice of the instructor filters through the smoke.

But no fireman leaves. The ground-level outside door is within reach of a hand. The hose plays on. The instructor drones on. There are coughs. But no fireman leaves.

“You can be a full-fledged fireman in Princeton, yet never have fought a real fire,” says Fire Chief Raymond Wadsworth. “For one guy today, this was a brand new experience. For others, they’ve had only limited exposure.

“In a big city, you could fight all kinds of fires in only a week. In a town like Princeton, the men don’t have a chance to get into certain conditions of fire-fighting.”

On a misty June Saturday, reporters were invited to join about 15 men from Princeton’s three volunteer fire companies in an all-day training exercise at the Burlington County Fire School. Although the school dates back to a 1974 $700,000 bond issue floated by Burlington, this was the first time any Princeton firefighters had gone there for training and practice.

“My training budget was cut in half — from $1,000 to $500,” Chief Wadsworth said ruefully. “It costs $100 to come down here to Burlington.”

Chief Wadsworth took the younger men to Burlington. They may not have had a chance to experience smoke, swirling blackness, the crackling reality of a fire. They are trained, of course, working with the foremen of the three companies. They also go to night school in Trenton, and must put in the required number of hours.

But a classroom isn’t the same.

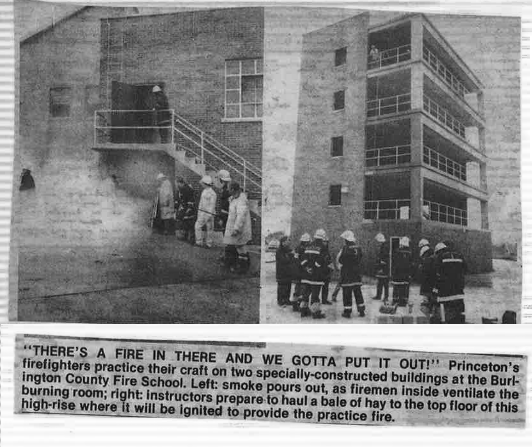

The Burlington Fire School campus looks like an amusement park in a horror movie. There is a five-story brick and concrete high-rise, black with char on the inside, its stairwells acrid with ancient smoke. A duplex brick house, a gutted ruin except for its sturdy interior walls, invites the next fire. Burned-out cars, in a row, have gone up in flames often, and will again. A square pond, when you pour

on its water, is a ready-made laboratory. You could even practice roof-top rescue

with a battered helicopter.

There is a special “smoke house,’’ but it’s out of commission temporarily. In a fit of irony, it was seriously damaged by fire. The small building, made of brick like all the others, had a plywood labyrinth inside. Its platforms and doors were designed to train firemen how to find their way when there is no way to be seen. (Using either your right hand or your left — but never switching, once you’ve chosen — feel your way around every comer.)

The first exercise was on the high-rise. Using a rope to haul up bales of hay donated by Rosedale Mills, firemen and, the Burlington instructors started a brisk blaze on the top floor. While the arsonists were at work, the first team of men on the grass down below began to suit up, buckling up their coats, pulling on the tall rubber boots, adjusting the new Scott Air-pak masks and securing the new hard-hat helmets that can even protect you from a falling beam, unlike the old-fashioned firemen’s hat.

These new masks, by the way, are 20 pounds lighter than the old ones, with a tank that provides more compressed air, even though it is smaller

An Air-pak lasts 30 minutes, 20 if you’re breathing heavily. A bell gives you a three-to- five-minute warning that you need another tank of air. When you hear it, you make your way out of the building, groping through the smoke and the dark by following the fire hose. You get new compressed air from the First Aid and Rescue Squad truck, present at Burlington as at all fires.

The first team of four, led by an experienced foreman from one of the companies, enters the burning building and climbs the stairwells to the floor below the fire. Here, they hook their hose into the standpipe and get to work.

After the fire is out, they emerge from the ground-floor door. They roll up their hose carefully. They fill their Air-paks to get ready for the next “fire”, and the second team moves in on the newly-ignited hay.

Princeton’s firemen put out fires together. You may be working with somebody from your company, maybe not. The traditional rivalry among Princeton Engine No. 1 (Chestnut Street Firehouse), Mercer Engine No. 3 (Chambers Street Firehouse) and Hook and Ladder (Norths Harrison Street Firehouse)] does not carry into the burning building.

Next exercise (the Burlington instructor says they, call it, for no reason he knows an “evolution”) is a cellar fire.

For this one, they move into the duplex brick house, laying straw down the stairs and on the cellar floor. Firemen, again in teams, enter from the outside. Wearing their masks, they make their way through the fire and down into the cellar.

Suddenly, in this exercise, one man appears at the head of the outside stairs. Another fireman is with him. The man holds the stair-railing and slowly makes his way to the bottom. Chief Wadsworth runs over, takes the man’s arm and leads him to a seat on the moist grass.

“He’d used up his air,” the chief explains.

But he’s back in action, for the next drill.

The duplex house is a macabre kind of fun-house. Myriad small rooms … turning hallways … an elevator shaft… closets everywhere … narrow walls concealing an electrical fire … a burnt

Continued on Page 12B

Firemen

Continued from Page 1B

refrigerator, stove, metal bed.

The instructors start the fire. The men don’t know, when they enter, what kind of game the instructors have set for them — as in a real fire — so they must look everywhere.

In two lines of four men each, one line to a floor, the men enter the burning house and vanish. All you can see, from the outside, is smoke coming out the window.

“There’s so much smoke inside you can’t see. so all you can do is go in there and dig for it,” Chief Wadsworth explains. watching to see how quickly the smoke dissipates. “If it dissipates quickly, they did it If it doesn’t, then they missed something.”

It dissipates in about three minutes. They didn’t miss a thing.

As the exercises proceed, the Burlington instructor watches and teaches.

“Open that door v-e-r-y slowly,” he says with emphasis. “Feel the door: if it’s hot — don’t open it.”

In the one “evolution” reporters are allowed to join, only one fireman wears the Scott Air-pak. He is the one with the hose. The purpose of the exercise is to show why it’s a good idea to play the hose on the ceiling, rather than on the fire itself. And incidentally, it is a lesson in smoke.

In the dark, ground-floor room, about the size of a living-room, bales of hay are ignited at one side, facing the firemen. The instructor, who had described what was going to happen, points out how the flames climb up the wall, then lick out toward you across the ceiling.

You train the hose, not on the flames themselves, but on the ceiling, “to cool it up there.” With the heat so reduced, he explains, you can stay longer in the burning room.

Just at the right moment, he directs the fireman to send a stream of water out the window. This creates a vacuum — you can feel it with your hand — and sucks out the smoke.

Before this drill, the instructor tells the men to leave if they feel sick from the smoke. There is no macho, no scorn for anyone who might want to leave. It is a learning session, not a proving ground.

The men are young, in their twenties or thirties, yet they are visibly tired after each exercise. The Burlington instructor warns them at the beginning: any horseplay and you’re OUT.

But there is none. Only quiet excitement and barely suppressed eagerness. At lunchtime, it’s soft drinks and not beer. After lunch, it’s more smoke. And at the end of the day, a renewed sense of professionalism, a sense of the baptism of fire.

—Katharine H. Bretnall

Photo Caption:

“THERE’S A FIRE IN THERE AND WE GOTTA PUT IT OUT!” Princeton’s firefighters practice their craft on two specially-constructed buildings at the Burlington County Fire School. Left smoke pours out, as firemen inside ventilate the burning room; right: instructors prepare to haul a bale of hay to the top floor of this high-rise where it will be ignited to provide the practice fire.